Agilent looks back at “Mr. Microwave”

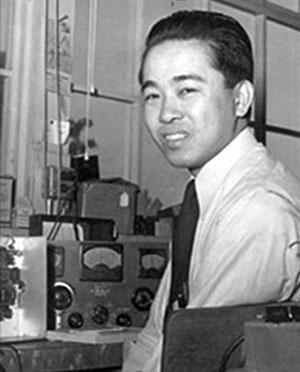

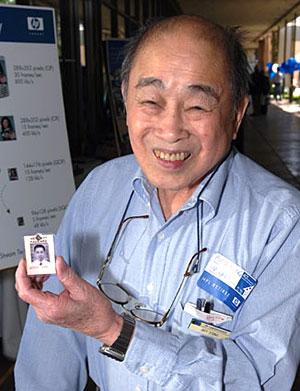

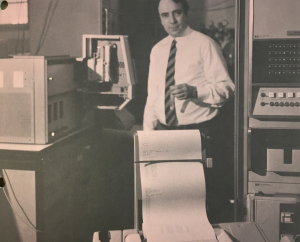

July 24, 2012 – Agilent salutes the life of Art Fong, who passed away earlier this year. Although Art retired from Hewlett-Packard before Agilent was launched, he is a critical part of our company’s history. Art was the sixth R&D engineer hired by HP in the 1940s and the company’s first Asian-American employee. When he passed away, his memorial service was hosted at Agilent headquarters in Santa Clara, Calif.

Over his long career, Art was responsible for many of the inventions and innovations behind Agilent’s current measurement technologies. In the mid 1960s, 27 percent of HP’s total revenue came from his designs. Attenuators that he designed in 1959 were still listed in Agilent’s 2005 product catalog. These accomplishments earned him the HP nickname “Mr. Microwave.”

“Art’s career at HP is legendary,” says John Minck, a fellow HP engineer and the company’s unofficial historian. “From a long list of signal generators across the microwave spectrum to the blockbuster HP 8551A spectrum analyzer, Art’s project leadership was unparalleled in microwave test equipment annals.

“His decades at Hewlett-Packard gave HP significant revenues, which helped enormously in the company’s stellar growth in the mid-20th century.”

“Art was a role model for all HP engineers,” says retired Agilent CEO Ned Barnholt. “He was smart, innovative and a team player who was always willing to help others. He was also down to earth and a real nice guy. He will be missed.”

A lifetime of contribution

Art Fong was born in Sacramento, Calif., in 1920, the son of Chinese immigrants. He was expected to follow his father in the family’s grocery business, but instead he went to college at the University of California in Los Angeles and in Berkeley.

While Art was attending UC Berkeley, the United States entered World War II. After receiving his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1943, Art moved to Boston to fulfill his Navy commission. He did research for the U.S. Department of Defense at the MIT Radiation Laboratory, where he contributed to the development of radar.

Another California technologist, Bill Hewlett, was serving in the Army Signal Corps and heard of Art’s radar work. In 1946, after the end of the war, Bill visited Art and offered him a job at Bill’s small startup, Hewlett-Packard. The deal was finalized that evening with a handshake. Art never even asked about salary until he showed up for his first day of work in California.

Art served HP for the next 50 years—40 years as an employee until he retired, followed by 10 years as a consultant. Over that time, he made significant engineering contributions to HP and the measurement industry, including impedance-measuring instruments, a line of signal generators, and the first calibrated microwave spectrum analyzer.

An invention ahead of its time

Among Art’s most important and interesting innovations were his contributions to radar technology.

“While we were at MIT Labs we had talked about [a police radar] with various people, but nobody had built one,” Art recalled in a 2009 interview. “I got to HP [and one day] I was up in San Francisco in one of those surplus stores. I saw all that x-band gear up there, and for fun I bought a parabola to build one.

“One coffee break we all went outside and I wanted to show the radar. Hewlett even joined us for a bit and said, ‘That’s real nice, Art, but we don’t want to make something like that. We’re in the instrument business.’

“It was about 20 years later before the commercial police radar came out. Of course, they’re a lot smaller. The one I made just helped prove that the idea was there.”

From the HP blog, “The Next Bench.”

“Dad loved working for HP,” Art’s daughter Sheryl recalls. “It was the perfect place for someone who was smart, creative and hardworking and was given the freedom to work on a project to its completion.”

Throughout his life, Art remained modest about his many contributions. “I was just one of the guys,” he said about his years at HP. “What drives me is I like to see something work.”

Art and his wife, Mary, established scholarships and fellowships for UC Berkeley and Stanford. Their many philanthropic contributions went to places such as the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Stanford Hospital and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

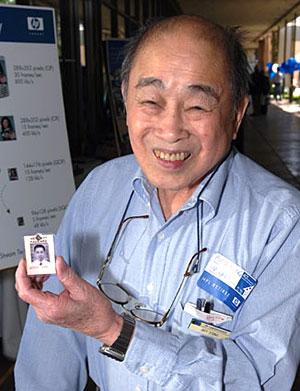

Art passed away peacefully at his home on May 17, 2012, at the age of 92.

A celebration of life

Art’s memorial service included his wife of 69 years, his four children, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Guests also included many long-time employees of HP and Agilent.

“Art never changed, he never seemed to age,” said retired HP Vice President Paul Ely. “Throughout his life he continued to exemplify integrity, trust and the best of the HP Way. Art brought peace, calm and laughter to all around him. It’s no wonder he was so widely admired.”

“His engineering style was always helpful, his vision clear and concise,” John Minck recalled. “I still remember Art, when asked a typically uninformed marketing question by me, would pull out pencil and paper and in a very small script and diagrams lead me to the right answer for a customer.”

“I was at the management meeting where [HP Manufacturing Vice President] Bruce Wholey was forecasting the size of the spectrum analyzer market,” said Alan Bagley, another coworker. “He wanted to show that Art’s new instrument would be very profitable if it only reached 40 percent of the market.

“A year or two later, HP had reached 300 percent of that projected market number. What Art had done was redefine what a spectrum analyzer was. The Hewlett-Packard Company had to form a new division to handle the business.”

Interesting facts

- Art had the same birthday—February 11—as famed inventor Thomas Edison.

- Art had no plans to attend college. One of his high school teachers, convinced of Art’s potential, applied to UCLA for him.

- While working at MIT during WWII, Art also moonlighted at the Browning Laboratories, where he developed the first AM/FM radio receiver.

- As the first Asian-American technologist in Silicon Valley, Art faced many cultural barriers. In 1946, it was illegal for Chinese-Americans to rent or buy property in desirable areas of Palo Alto, Calif. Art had to purchase his property near the city limits.

- Art didn’t earn a master’s degree in electrical engineering until 1968, from Stanford University.

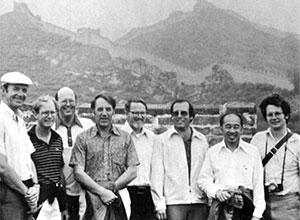

- In 1979, Art went with HP President John Young to the just-opened People’s Republic of China as a technology lecturer. He would return to China three more times to help the country come up to speed on engineering innovations.

One of the best stories came from Art’s grandson, Christopher Wong, about a time his grandfather was caught speeding:

“Grandpa was ‘coasting’ probably around 75 or 80 miles per hour down this stretch, and sure enough there was a highway patrol officer waiting at the bottom to catch us.

“After stopping us, the female patrol officer walked up to the door and asked Grandpa, ‘Hi, sir, do you know how fast you were going?’ to which he responded innocently, ‘I don’t know officer, but it was probably a little fast.’ She pulled out her radar gun and it showed his speed limit easily being over the 45 mile per hour limit for the road.

“He smiled. ‘Hey, did you know I helped invent radar?’ he said very matter-of-factly.

“She looked at him skeptically. ‘Yeah, I’m sure you did.’

“Well, this was Grandpa’s cue, and he launched into his back story about his time as a young engineer at MIT in the midst of WWII working on secret projects, complete with details, all while she started to write him up a ticket. She nodded courteously as he went on with the story, but clearly she wasn’t buying it as an excuse out of the ticket.

“As he wrapped up the story, she handed him the ticket. She said, ‘That’s a nice story, sir. Here’s your ticket. You’ll receive further notice of instructions in the mail in two to three weeks.’

“‘What, you don’t believe me?’ my grandpa replied, exasperated.

“‘Uh, no. But I wrote you a ticket for speeding 50 in a 45 zone, rather than 75 in a 45 zone, since you were so entertaining.’”

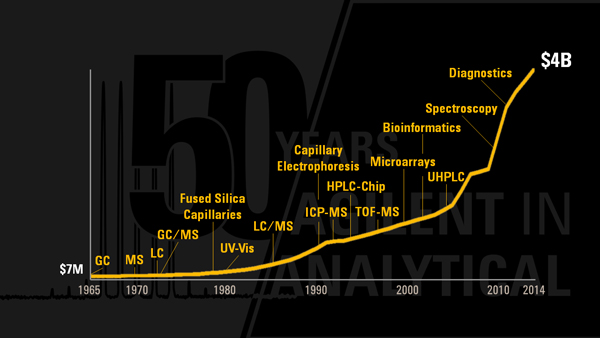

Agilent History Timeline

Today, Agilent remains a leader in gas chromatography, liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Ever since Agilent’s chemical analysis product was selected for the 1972 Olympics, the company has been the major supplier of drug-testing equipment for elite sports competitions worldwide, including the World Cup and the Tour de France. Agilent also provides drug-testing solutions to law enforcement and forensics laboratories worldwide that allow scientists to identify, confirm and quantify thousands of substances in a wide variety of samples.

Today, Agilent remains a leader in gas chromatography, liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Ever since Agilent’s chemical analysis product was selected for the 1972 Olympics, the company has been the major supplier of drug-testing equipment for elite sports competitions worldwide, including the World Cup and the Tour de France. Agilent also provides drug-testing solutions to law enforcement and forensics laboratories worldwide that allow scientists to identify, confirm and quantify thousands of substances in a wide variety of samples.