Performance enhancement has been on the minds of athletes for over 2,000 years. Its origins can be traced back to the ancient Olympics, where athletes would eat specially prepared lizard meat, hoping it would give them the winning edge.

By the 20th century, Olympic athletes were using testosterone, and the term “doping” had come into use. As methods to increase performance became more extreme and winning more political, it became evident that the use of performance-enhancing drugs was a threat to the integrity of sport and could have potentially fatal side effects if not stopped.

At the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, Danish cyclist Knud Enemark Jensen fell from his bicycle and later died. A coroner’s inquiry found he was under the influence of amphetamine, which caused him to lose consciousness during the race. This has been the only Olympic death linked to doping.

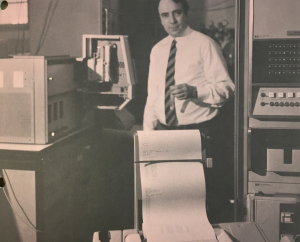

By 1972, the Olympics in Munich began drug testing on a broader scale. At the heart of the scrutinizing process were eight HP 7600A Gas Chromatographs, used to screen urine samples taken from randomly selected athletes after each event.

Dr. Manfred Donike, a German scientist, began the first full-scale testing of athletes at the Munich games. Using the HP 7600A, he reduced the screening process from 15 steps to three. His method was considered so accurate that no outside challenges to his findings were allowed.

At the 1983 Pan American Games in Caracas, Venezuela, Donike’s laboratory disqualified 19 athletes; many other competitors withdrew before they were due to be tested. At the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, Korea, Donike’s testimony—based on a screening method using the HP 5970 Mass Selective Detector—led to the suspension of Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson. (When Johnson’s defenders claimed that unknown parties had somehow spiked the athlete’s drink, Donike declared, “How can anyone seriously state such nonsense?”)

Donike died of a heart attack on Aug. 21, 1995, at age 61. “His contributions over the past 25 years have been innumerable,” said UCLA’s Dr. Don Catlin, a pioneer in modern drug-testing for sports. “He devised all the chemical methods of identifying prohibited substances.”

In 1997, HP established the Manfred Donike Award to recognize “scientists who exemplify the spirit and scientific leadership of doping control pioneer Manfred Donike, and whose contributions significantly increase fairness in sports competition.” The award continues to be given annually by Agilent.

Today, Agilent remains a leader in gas chromatography, liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Ever since Agilent’s chemical analysis product was selected for the 1972 Olympics, the company has been the major supplier of drug-testing equipment for elite sports competitions worldwide, including the World Cup and the Tour de France. Agilent also provides drug-testing solutions to law enforcement and forensics laboratories worldwide that allow scientists to identify, confirm and quantify thousands of substances in a wide variety of samples.

Today, Agilent remains a leader in gas chromatography, liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Ever since Agilent’s chemical analysis product was selected for the 1972 Olympics, the company has been the major supplier of drug-testing equipment for elite sports competitions worldwide, including the World Cup and the Tour de France. Agilent also provides drug-testing solutions to law enforcement and forensics laboratories worldwide that allow scientists to identify, confirm and quantify thousands of substances in a wide variety of samples.

For more information go to;

- Obituary: Sport-drug Foe Manfred Donike, 61 (Chicago Tribune)

- The detection of doping by means of chromatographic methods

- Drug Use in Sports: Pros and Cons

- Hacking your body: Lance Armstrong and the science of doping (The Verge)

- They’re not playing games in Munich (HP Employee Magazine)

- Agilent Technologies in Sports Drug Testing

- Proven Screening Methods for Identifying Banned Substances in Sports

- Solutions That Meet Your Demands for Forensics & Toxicology: Doping Control Compendium

- Sports Doping (Agilent infographic)